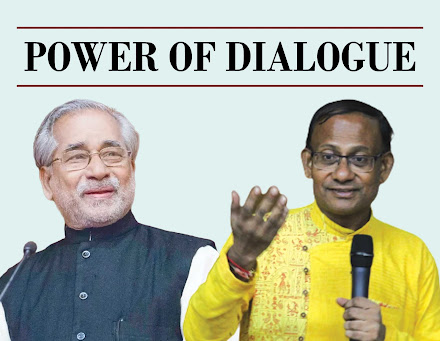

POWER OF DIALOGUE

Professor N. Radhakrishnan, Gandhian Scholar and former Director of Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti, New Delhi.

(Reproduced below is a

conversation Dr. Vedabhyas Kundu, Program Director of GSDS( New Delhi) had with Prof.Neelakanta

Radhakrishnan, published recently in the book, Peace and Nonviolence)

Vedabhyas Kundu: In your dialogue with eminent peace scholar Daisaku

Ikeda in the book Walking with the

Mahatma: Gandhi For the Modern Times,

Dr. Ikeda succinctly points out, "A master of dialogue, Mahatma Gandhi urged keeping the window of

the mind open at all times." Please elaborate on the Gandhian approach to

dialogue for peace.

N Radhakrishnan: Thank you Dr. Vedabhyas for your reference to the much-talked-about book that grew out of the dialogues Dr. Daisaku Ikeda, President of

Soka Gakkai International, and I had over several years in different parts of

the world on. Gandhi and contemporary world issues. It is significant that Dr. Ikeda, himself a master of dialogue and who has the distinction of holding over 2,000

dialogues with outstanding personalities of the world, rightly describes Gandhi as

"a mast', of dialogue." Gandhi's advocacy and practice of dialogue in

fostering an era of nonviolent communication and leadership remains an important area to

explore.

As any diligent reader will

note, Dr. Ikeda argues passionately in our dialogue that Gandhi used the medium

of dialogue with consummate dexterity and skill. The journals and newspapers

Gandhi edited both in South Africa and India were essentially channels of

communication for him with the readers. Gandhi invited questions and answers and

even published the views and articles against him I his own journals which were

run on ethical and moral grounds and were most in the form of dialogue.

The two books by Gandhi that give the most

valuable basic details of his lif and work are My Experiments with Truth (an autobiography) and Hind Swaraj, small treatise that

attracted enormous hostile criticism besides being banned the British for the

"seditious views it contained." Even his trusted disciple, Jawaharlal Nehru, advised

him to withdraw the book. Gandhi differed with all his critics and remained

firm on his position. It was significant that when it was reissued after several

years, Gandhi did not change a single word.

The Hind Swaraj is in the form

of a dialogue between an editor and a reader. The dialogue raised several

issues of contemporary relevance, such as an alternative vision for the

industrial-urban society of India, the deepening civilisational crisis, the escalation of violence,

problems of marginalization, strategies of nonviolent resistance, development with

justice and peace, peaceful co-existence of different religions et cetera.

In this book, Gandhi also introduces his

famous distinction between religion as organization and religion as

ethics and spiritually. He stresses that, underlying all organized religions,

there is a universal ethics and spiritually, which teaches the unconditional love of God

and one's neighbour. At the same time, religion as organization serves as a

convenient means of maintaining a certain type of pre-political identity. Every

organized religion is able to get a certain amount of legitimacy. It follows

that organized religions ought to practise tolerance towards each other. Hind Swaraj thus convincingly argues

that there are good religious reasons for practicing tolerance.

Anthony J Parel, in his analysis of the book makes an interesting observation

in this

context : "Three strands of thought on nonviolence are present in Hind Swaraj. The first is that

involuntary violence is consistent with Gandhian nonviolence. 'Going to the root of the

matter,' Gandhi writes, 'not one man really practices such a religion (of ahimsa) because we do destroy life. We

are said to follow that religion (of ahimsa) because we want to obtain freedom from the liability to destroy any kind of life.'

In other words, what the ethics of nonviolence seeks is the freedom from moral

capability for the sort of necessary involuntary violence that ordinary embodied life

entails. The second strand concerns the intention for an act to be violent in

the Gandhian sense, an intention to harm another living being has to be present. Thus, for

example, the act of restraining a child rushing into a fire is only apparently violent, 'I

hope you will not consider that it is still physical force, even if of a low

order, when you would forcibly prevent the child from rushing towards the fire if you

could: The third strand has to do with legitimate self-defense: self-defense

within the limits of natural justice is consistent with nonviolence. Gandhian

nonviolence expects the just state to be the guarantor of internal peace and external

security. What is inconsistent with nonviolence is the principle of raison d'Etat that refuses to recognise

the higher law of dharma, namely the behavior of the modern state when

it purses policies on the basis of in allegedly autonomous national interest."

It is significant that Gandhi also viewed dialogue and the shared

understanding that might result from it as one of the most powerful human

actions for promoting an authentic culture of peace and conflict

reduction techniques, His work and struggle for human rights and peace in South

Africa for 21 years and the unprecedented mass upheaval through nonviolent mass

agitation and constructive work for national freedom of India which lasted 32

years offer very valuable lessons to humanity in the context of growing

conflicts that bedevil most of the countries and societies today.

It may also be remembered that the strategies

Gandhi evolved were mostly based on his profound understanding of the power of

dialogue that according to him was much more than two individuals talking to

each other in an attempt to understand each other or sort out outstanding

differences of opinion. The dialogues of masters such as Socrates and Plato in

ancient times offered precious insights into the complex nature of what

constitutes human behaviour vis-à-vis human aspiration, which many later

visionaries and social activists interpreted in the light of the evolving

socio-political scenario, Honest attempts were made by many evangelists of

dialogue to the collective treasures of acknowledging differences, discovering

our common humanity, and achieving a new understanding as the basis for mutual

cooperation. It is this precious jewel of heart-to-heart dialogue that makes

dialogue as the potent and productive weapon in the arsenal of nonviolent peace

builders.

The former Secretary-General

of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon had once stressed, "Intercultural

dialogue could promote reconciliation in the aftermath of conflict and could

also introduce moderate voices into polarised debates." What kind of

framework of dialogue do you envision that can be encouraged for reconciliation

and forgiveness? How can we encourage young people to enter intu, dialogue

whenever any differences or conflicts arise?

Well Dr. Vedabhyas, I am happy to see that far from being

an academic type of exchange of ideas, the Ikeda – Radhakrishnan dialogue

gradually assumes the level of a live dialogue on certain pivotal areas as Ban

Ki-moon has rightly stressed. I fully

concur with him when he argues that what’s required now in an honest attempt to

identify the skills and spirit that make dialogue possible at all levels and

among all types of people, an attempt has to necessarily take into acount the

humanity in each person, respect for each tradition, tolerance towards the

multi- ehnic, multi-religious nature of modern societies and nations. And it has to be intercultural in all

respects.

Gandhi’s efforts for a

nonviolent society were characterized by both individual and societal change as

an essential rquisite for transformation.

The manner in which leaders such as Martin Luther King(Jr). Nelson

Mandela, Ho Chi Minh, Rosa Parks, Petra Kelly, Aung Sung Suu Kyi, Lech Walesa,

Mubarak Awad, Mairead Maguire, the martyred Antioquia Governor Guillermo,

Professor Glenn D Paige, and many other champions of nonviolence who adapted the

Gandhian techniques of conflict resolution through positive and affirmative

human action need to be understood in this perspective.

The mounting conflicts

of various kinds prevalent in almost all societies and countries of world today call for

honest and concerted efforts if humanity has to survive. The Truth and Reconciliation

Commission, led by Bishop Tutu in South Africa, and the lessons humanity may learn

from this highly bold and imaginative step to conflict reduction and

nation-building, unfortunately, has not been properly understood by the rest of humanity. We

also have to learn from the pioneering efforts of Dr Daisaku Ikeda whose Herculean

efforts to promote dialogue for global peace and sustainable development have

assumed supreme importance globally. Dr Daisaku Ikeda has been employing

dialogue as a very effective strategy in promoting awareness among people. Engaging in dialogues with

the best brains in different fields in different parts of the world in an

attempt to share, analyse, focus, and critically examine common concerns id issues which are arising

out of human endeavours has been found to be extremelyful. I always remember the

assertion of Dr Ikeda, "If one drop of the water of

alogue

is allowed to fall upon the wasteland of intolerance, where attitudes of

hatredd exclusionism have so long prevailed, there will be a possibility for

trust and andship to spring up. This, I believe, is the most trustworthy and

lasting road to that al. Therefore, I encourage the flow of dialogue not only

on political plane but also the broader level of the populace as a

whole."

Every session of our

dialogue, every thought and moment I spent with Dr Ikeda at*rent occasions since 1984

was education to me and elevating and inspiring. One once that has been immersed

into my being perhaps sums up his entire life and Iribution to humanity:

"If you are afraid of persecution and defamation, you cannot II the doors on a new

age". The manner in which Ikeda has been making use of the lurn of dialogue to bring

people together and foster goodwill and peace sums up henomenal success in

developing the art of dialogue and giving it "a name and habitat" as Shakespeare

would have called it, had he been alive today.

Over the last seven decades,

Dr Ikeda is credited with a number of initiatives and igns that influenced the

United Nations and many governments across the to adopt his annual peace

proposals for world peace, sustainable development flues, disarmament,

environmental protection, educational reforms, human rights tion, gender equity, and

better religious understanding. The new world order that Revolution initiated by the

SGI under Dr Ikeda envisions among many thrust areas at individual and

collective level, seeks to encourage global efforts to ensure human rights,

strengthening of people's initiatives, and the emergence of a global outlook.

Humanities longing for peace has to be nurtured at all costs. Global

initiatives such as the UN symbolizing the shared longing of humanity for peace

and justice are to be nurtured. By doing so, we are only ensuring the right of

humanity to exist, prosper, and help people discover their full potentials. One

of the pre-requisites for this is dialogue, both the "inner" and

"outer" dialogue.

The theme of human

survival has been central to the various dialogues Dr Ikeda has been holding

with intellectuals, political, social, and artistic giants of the world during

the last seven decades with passionate conviction. There is so much violence,

crime, hatred, and exploitation in the world today and one of the major reasons

of this is the lack of communication, dialogue, and trust. Dr Ikeda's dialogues

have demonstrated once again in recent times how decision makers,

intellectuals, philosophers, artists,religious leaders, diplomats,

revolutionary thinkers, and a whole lot of others could be engaged in

qualitative discussions. In effect, these dialogues have been found to be the

genuine seeds of "Human Revolution."

Very few before him seem

to have used dialogue as an effective strategy in promoting awareness among

people. Engaging in dialogues with the best brains in different fields in

different parts of the world in an attempt to share, analyse, focus,and

critically examine common concerns and issues that are arising out of

contemporary developments in various fields of human endeavours has been found

to be extremely useful and rewarding. The outstanding quality of each of his

dialogue is the highly creative manner in which Ikeda is able to discuss the

various issues from different perspectives without a trace of repetition — a

remarkable and rare achievement — and linked to what he believes is paramount

importance to humanity's survival. In his words, "I love people. That is

why I meet and talk with people from all walks of life. Dialogue transcends

ethnic and ideological differences. I will continue to engage in dialogue as

long as I live. We must never stop promoting dialogue across cultures. In a

sense, dialogue is an earnest struggle between two people. It could even be

described as sparring with words. It is through this process that both parties

begin to open their hearts to one another."I am convinced and glad to

state here that Dr Ikeda has influenced quite a few statespeople, scientists,

artists, human rights activists, peace promoters, scholars, and others cross

the world through his dialogues. He has held over 1,500 dialogues durin the

last four decades with remarkable felicity and elan. He could claim distinction

for raising the genre of dialogue to higher levels since Socrates and Plato.

My long association with

Dr Ikeda and his movement for peace and change has taught me many lessons, and

he has influenced me in both my personal life and public activities. Besides my

deepening admiration, I tend to look up to him for spiritualguidance as in him

I see a living Gandhi. Some of my activities in India have beeninfluenced by Dr

Ikeda. I am profoundly committed to the welfare of children, a lesson I learnt

from Dr Ikeda, and the two children's campuses working under my guidance are an

embodiment of this truth.

The Gandhi Peace Mission recently initiated a project to highlight the

importance of Dialogue, Reconciliation, and Justice as national objectives and

use them for effective conflict resolution activities. On the Hiroshima day of

2009, a new initiative with this locus was launched and it is known as the

Citizens' Commission for Dialogue, Justice and Reconciliation. This is

certainly due to his influence on me and many of us in India.

In a landmark initiative, the various Gandhian organizations in India

launched a two-year International Peace Campaign on 26 January, 2017, to mark

the occasion of 70th anniversary of Gandhi's Peace Mission in strife-torn

Bengal in 1946. The Gandhi Peace Mission, as it will be known, seeks to

highlight Dr Ikeda's favourite mission, Dialogue, Reconciliation, Justice and

Peace as the motto of the campaign. The date of launch was 26 January, India's

Republic Day and also the founding day of Soka Gakkai.

The two-year campaign

comprised a group of peace activists undertaking a goodwill visit to some of

the villages in Kolkata and Noakhali (now in Bangladesh) that bore the brunt of

communal orgy, large scale murder, looting, and violence. Gandhi had toured

these villages barefoot persuading people to use dialogue as a means to settle

disputes and end violence of all types. The participants of the Gandhi Goodwill

Mission sought to follow the path Gandhi had travelled in 1946 and on reaching

Noakhali

Olie epicentre of violence and killing) - about 600 kilometres away from

Kolkata and 300 kilometres away from Dhaka - prayer functions, and goodwill

interactive sessions woh local people, dialogue, and peace marches will be

held. The Goodwill Mission planned to attend the Gandhi Martyrdom prayer at

Gandhi Ashram at Jayag in Noakhali on 30 January and to interact with the

intellectuals, peace activists, women, and youth Aders in Dhaka the next day.

Back in Kolkata on 2 February, the Peace Mission would received by youth

leaders from different parts of India at a special Youth Assembly.

This was to be followed by an

International two-day Peace Summit on Role of Dialogue, Reconciliation,

Forgiveness, and Justice in Sustainable Peace and Development. Owing to sudden

political developments in Bangladesh, the visit to the Noakhali villages was

shelved while the International Peace Summit was held successfully in Kolkata

with participants from17 countries joining it.

Comments

Post a Comment